With new excavations in Pompeii, there are exciting finds being shared every few weeks. Pompeii stirs the public imagination like nothing else in antiquity (whether we like it or not) and each new find is assured its place in the news cycle. Pompeii, to the public at least, encapsulates Rome. All of it. The entire empire, over centuries. That's a forgivable misconception, and the clickbait articles that follow each announcement are devoid of any contextualisation.

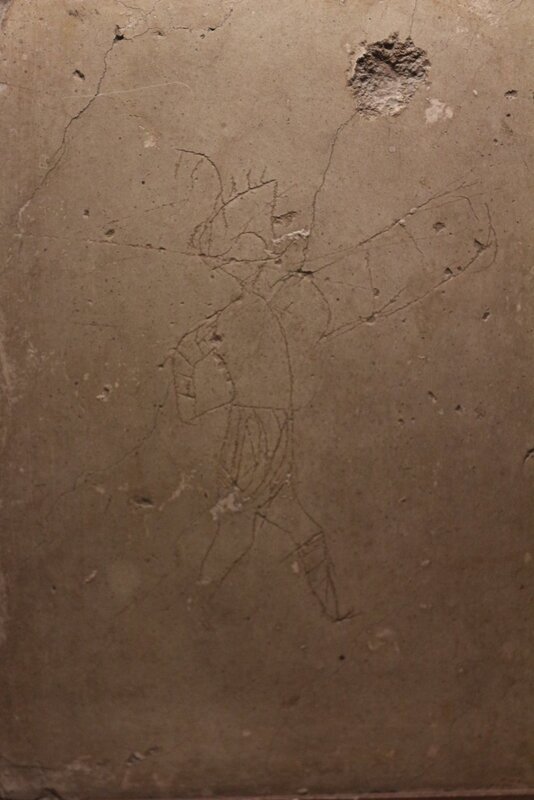

That's predictably true this week; excavations have found graffitied doodles of gladiators on a Pompeiian wall, close to the ground and with a simplistic style that can only the be work of little children. They're charcoal doodles, and it's all too easy to picture the kids scribbling on the walls when Mum wasn't looking, in what must have been only a few days or even hours before Vesuvius erupted. Archaeologists of Pompeii have written up a mini-report of the excavations of that particular building, if you fancy a read (in Italian.) Or, if you like, you can watch Gabriel Zuchtriegel (the current Director of the archaeological site) show you the drawings, complete with English subs:

That's predictably true this week; excavations have found graffitied doodles of gladiators on a Pompeiian wall, close to the ground and with a simplistic style that can only the be work of little children. They're charcoal doodles, and it's all too easy to picture the kids scribbling on the walls when Mum wasn't looking, in what must have been only a few days or even hours before Vesuvius erupted. Archaeologists of Pompeii have written up a mini-report of the excavations of that particular building, if you fancy a read (in Italian.) Or, if you like, you can watch Gabriel Zuchtriegel (the current Director of the archaeological site) show you the drawings, complete with English subs:

The children drawing these gladiatorial fights and arena hunts are young, perhaps five to seven, and the archaeologists, together with Italian psychologists, have decided that the kids are drawing what they've witnessed. That would mean they're not copying gladiatorial graffiti by adults, they're not looking at the professionally painted depictions of gladiators in Pompeiian art, or the gladiators carved in relief on Pompeiian tombs. This is evidence, they say, that children were spectating.

I'm on the fence about this. After all, Pompeii was full of gladiatorial art. Let's look at some, because why not? (All photos but the first are my own.)

I'm on the fence about this. After all, Pompeii was full of gladiatorial art. Let's look at some, because why not? (All photos but the first are my own.)

This is a fresco from a bar in Regio V, and was excavated in 2019. The match is over, and the gladiator on the right, bleeding profusely and utterly exhausted, is extending a finger to signal that he gives in. His fate (the nature of which depends on the stakes of the match) will be decided by the person presenting the Games. He could be spared and live to fight another day, or he could be killed. Click the photo to go to the official press announcement about this discovery.

This is a close up photo I took of a Pompeiian fresco now kept in the Archaeological Museum in Naples. It was found in the House of Anius Anicetus (I.3.23.) The whole fresco shows the Pompeii ampthitheatre in the middle of a famous riot between local fans and spectators who'd travelled from Nuceria twenty years before the eruption. The fans behaved so badly Pompeii was slapped with a ban on spectacles!

Thank goodness Francesco Morelli painted a copy of this fresco, found near the Porta Nola in Pompeii, when it was discovered in 1813; the fresco is long gone and this painting is all we have as evidence for it.

It wasn't just kids doodling gladiators - an adult Pompeiian scratched this one into a plastered wall.

This little terracotta murmillo was found at Pompeii; cheap little souvenirs of gladiators have been found all over the empire. Lamps were also wildly popular. This, I suppose, is the equivalent of an action figure!

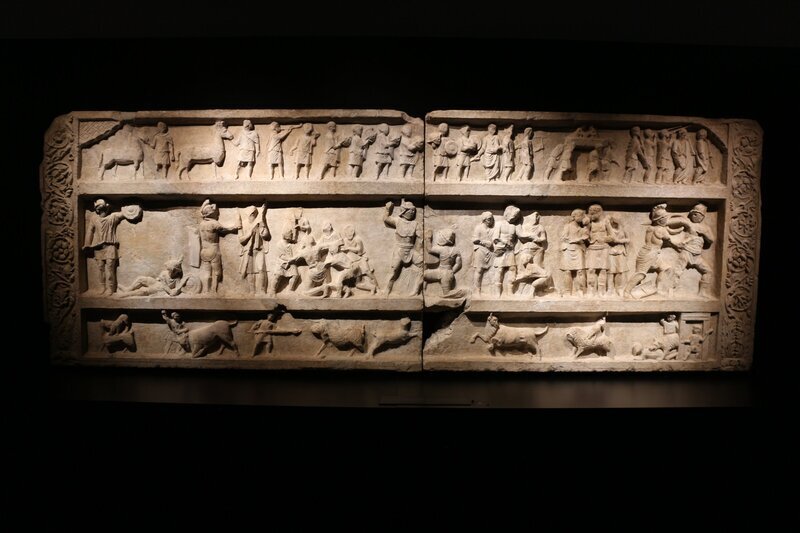

This massive relief was part of the funerary monument of a Pompeiian and was found in the necropolis outside of the Stabian Gate in 1854. It was in a prominent position to be viewed by passers by, and depicts an entire day of Games - the 'pompa' procession at the beginning, the beast hunts, and the gladiators. Archaeologists now think it was part of the monument to Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius, a prominent local politician. The base of the monument, (if the two do indeed belong together,) was finally excavated in 2017, and the inscription records that this politican paid for Games, earning himself some goodwill with voters and constituents.

My point is, Pompeiian children had lots of opportunities to see art of all kinds that depicted gladiators. So does their doodling mean that they were spectating, or just surrounded by images of a cultural mainstay?

It's open to interpretation, but it's an exciting window into Roman childhood all the same. You can almost picture them playing at gladiators in the atrium, using sticks for swords.

The archaeologists seem pretty convinced that the kids must have attended the amphitheatre, and that conviction has definitely convinced the press. Let's look at a few headlines and quotes:

"The youths’ vivid drawings illustrate the degree of violence to which they were casually exposed on a regular basis." - Smithsonian

"Today we have warnings on certain films and video games that are thought to be too adult for children to watch, but at the time that Pompeii was buried by the volcanic eruption, children would have seen gory things like gladiators fighting to the death!" - CBBC Newsround

"Newly discovered Pompeii graffiti reveals horrifying secret about brutal and bloody gladiator fights 2,000 years ago." - The Sun

"Shocking Pompeii Graffiti Exposes Brutal Truths of Ancient Gladiator Battles!" - Central Recorder

Comments on social media are less formal, with accusations of Romans being bad parents due to an insatiable bloodlust. Zuchtriegel rightly points out that modern children are exposed to violence too, but that hasn't stopped the accusations that Romans were particularly brutal in comparison. Naturally I have a few thoughts on this, and I aim not to defend Romans nor condone their behaviours - I merely seek to understand.

Firstly - as a parent and aunt, I have witnessed some weird drawings by young children. Some have some pretty heavy themes, and I vaguely remember drawing some pretty horrifying stuff myself. Children pick up on the culture around them and are exposed to darker aspects of life whether vicariously through entertainment, or from lived experience. They're negotiating discovering the birds and the bees, death, and everything in between and they're doing so with or without adult permission or encouragement, though I will suggest that shielding children merely stokes fascination. In the Roman world, such subjects were dealt with without the reticence of our modern, western societies, and were likely more conspicuous in day to day life. Most Pompeiian children would have been exposed to death early - mothers dying in childbirth, high infant mortality rates, and gnarly illnesses for which cures were not yet known. Again, I'm not saying that an amphitheatre was the ideal place to introduce children to the concept of mortality, but I am going to point out that Romans had to face death far more often than we do, which we can take for granted.

Secondly - beware of generalisations. This does not demonstrate that children watching gladiators was common even in Pompeii, let alone the whole empire throughout its entire existence - this demonstrates that one or two children may have attended at one point. We all know that one kid with a lax parent who had access to stuff we didn't even know existed and would never be allowed near ourselves. One parent =/= Roman parenting.

Thirdly - and most importantly - modern revulsion at children watching bloodsports comes from a long tradition of modern moralising; we're so busy being vocally disgusted by bloodsports that we don't spend the time seeking to understand them. It's easier, and lazier, to declare that Romans were bloodthirsty savages. That they exposed their children to guts and gore merely cements this idea in our imagination. But if we look deeper into why gladiators existed, it's a different picture altogether.

The arena wasn't a conveyor belt of mindless violence; it was a teaching tool. Gladiators existed to teach Romans how to be Roman. Think of it as ideology by stealth - 'edutainment.' In the amphitheatre, gladiators taught Romans several things:

For centuries, people have been and are still instilling nonsense into their young boys. For us, this is a pretty shocking example of it, but I can think of far worse examples from more recent history, like the Hitler Youth, or watching young Israeli children gleefully destroying aid shipments on lorries bound for the Gaza strip. These two examples are extreme, but they're examples that hopefully prompt us to try and understand the ideology that produced them rather than merely shake our heads. Nazis and Zionists aren't 'mindlessly' bloodthirsty, and most of them consider themselves civilised and morally sound. The Romans did too.

Perhaps knowing a little more about the ideology of the arena makes you more horrified that these children in Pompeii might have been watching real combats from the age of five. But when you think about it, children of all ages absorb or are explicitly taught some questionable stuff in every era, and that's how prejudice seeps into every new generation. Again, I'm not saying this is a good thing, but it's something that we need to delve deeper into in order to understand.

Perhaps, rather than clutching our pearls at the 'barbarity' of the past, we can use this to pause for a moment and consider what we're instilling into our own children in the 21st century, explicitly or otherwise. What messages are we giving them about our own concepts of gender roles? What are the virtues we urge them to foster? How are we answering the questions they are asking about life and death? What forms of entertainment do we deem appropriate? What levels of violence and dehumanisation do we deem socially acceptable? Who are we teaching our children to trust, whose authority to unquestionably accept? And this one is particularly relevant right now: whose deaths are we saying it is OK to witness or even cause?

wly discovered Pompeii graffiti reveals horrifying secret about brutal and bloody gladiator fights 2,000 years ago

It's open to interpretation, but it's an exciting window into Roman childhood all the same. You can almost picture them playing at gladiators in the atrium, using sticks for swords.

The archaeologists seem pretty convinced that the kids must have attended the amphitheatre, and that conviction has definitely convinced the press. Let's look at a few headlines and quotes:

"The youths’ vivid drawings illustrate the degree of violence to which they were casually exposed on a regular basis." - Smithsonian

"Today we have warnings on certain films and video games that are thought to be too adult for children to watch, but at the time that Pompeii was buried by the volcanic eruption, children would have seen gory things like gladiators fighting to the death!" - CBBC Newsround

"Newly discovered Pompeii graffiti reveals horrifying secret about brutal and bloody gladiator fights 2,000 years ago." - The Sun

"Shocking Pompeii Graffiti Exposes Brutal Truths of Ancient Gladiator Battles!" - Central Recorder

Comments on social media are less formal, with accusations of Romans being bad parents due to an insatiable bloodlust. Zuchtriegel rightly points out that modern children are exposed to violence too, but that hasn't stopped the accusations that Romans were particularly brutal in comparison. Naturally I have a few thoughts on this, and I aim not to defend Romans nor condone their behaviours - I merely seek to understand.

Firstly - as a parent and aunt, I have witnessed some weird drawings by young children. Some have some pretty heavy themes, and I vaguely remember drawing some pretty horrifying stuff myself. Children pick up on the culture around them and are exposed to darker aspects of life whether vicariously through entertainment, or from lived experience. They're negotiating discovering the birds and the bees, death, and everything in between and they're doing so with or without adult permission or encouragement, though I will suggest that shielding children merely stokes fascination. In the Roman world, such subjects were dealt with without the reticence of our modern, western societies, and were likely more conspicuous in day to day life. Most Pompeiian children would have been exposed to death early - mothers dying in childbirth, high infant mortality rates, and gnarly illnesses for which cures were not yet known. Again, I'm not saying that an amphitheatre was the ideal place to introduce children to the concept of mortality, but I am going to point out that Romans had to face death far more often than we do, which we can take for granted.

Secondly - beware of generalisations. This does not demonstrate that children watching gladiators was common even in Pompeii, let alone the whole empire throughout its entire existence - this demonstrates that one or two children may have attended at one point. We all know that one kid with a lax parent who had access to stuff we didn't even know existed and would never be allowed near ourselves. One parent =/= Roman parenting.

Thirdly - and most importantly - modern revulsion at children watching bloodsports comes from a long tradition of modern moralising; we're so busy being vocally disgusted by bloodsports that we don't spend the time seeking to understand them. It's easier, and lazier, to declare that Romans were bloodthirsty savages. That they exposed their children to guts and gore merely cements this idea in our imagination. But if we look deeper into why gladiators existed, it's a different picture altogether.

The arena wasn't a conveyor belt of mindless violence; it was a teaching tool. Gladiators existed to teach Romans how to be Roman. Think of it as ideology by stealth - 'edutainment.' In the amphitheatre, gladiators taught Romans several things:

- Martial excellence. Rome loved a bit of war, and needed a huge amount of soldiers to feed its habit. In the early days, they were citizen soldiers who'd leave their farms and workshops to pick up a sword and go on campaign for a couple of months each year. Before long, the army was a bona fide force of professional soldiers. Gladiators were a how-to display of all the skills that came in handy on a battlefield, and a reminder to all Romans of exactly how a small town in Latium had turned into a massive empire. Gladiators were even used to train troops on occasion, teaching them tactics and tricks that gave them an edge over enemies. If you think that the American military obsession is OTT, they ain't got nothing on Rome. And think about it - to keep that pro-war sentiment going and recruitment high, you need to do a couple of things - one is to make war look like a grand adventure, and to instill that thirst for glory in the kids you want to fight your wars for you. I had a full set of Playmobil knights when I was a kid, my brother had Action Men, you may have had a G.I. Joe, Pixar included that bucket of soldier figurines in the Toy Story movies. My daughter has quite the armoury of foam medieval weapons purchased from various castle giftshops... for Romans, gladiators made combat look cool.

- Masculinity. We'd call this toxic masculinity now and it definitely is to our (incredibly recent) modern sensibilities, but then again we'd be considered pansies by most Romans. Gladiators also functioned as a demonstration of expected gender roles. There were a couple of personality traits that Romans wanted to instil in little boys and grown men alike, and the term virtus was an umbrella term for all of them: courage in the face of danger, self discipline, martial prowess, et cetera. Virtus wasn't just applicable to battlefields but to all facets of life, and gladiators were the live demonstration of putting virtus into practice. They were brave, they were skilled, they were tough. Most importantly, as a lot of them were enslaved, prisoners of war or criminals, they provided a convenient low bar for which spectators. If the scum of the earth could demonstrate such excellence inside the arena, well then ordinary Romans had no excuse not to be even more excellent outside of it.

- Domination. Gladiators in the early days were styled and named after 'barbarian' enemies of Rome. One type was the Samnite, was a facsimile of a defeated foe indigenous to the region Pompeii was in. Pompeii wasn't a Roman town, it was taken over after the Romans pummelled the bejeezus out of it in a massive siege. Samnites were phased out to avoid offence, and became a new type of gladiator with an innocuous name. However, the point still stands, particularly when we remember that gladiators were largely purchased or recruited by the lowest of society, that gladiators were a demonstration that Rome always, always won. Not only did it enjoy reminding itself of its own military and imperial domination, it liked reminding those it dominated of their place. Rome filled its arenas with men and animals from lands as far as it could reach, and had final say over their fates. The moral of the story? Don't question Rome's authority, they're large and in charge and they will absolutely squash you like an ant. Pompeii's amphitheatre was built only a decade after that siege, a visual reminder and demonstration of Roman imperialism.

For centuries, people have been and are still instilling nonsense into their young boys. For us, this is a pretty shocking example of it, but I can think of far worse examples from more recent history, like the Hitler Youth, or watching young Israeli children gleefully destroying aid shipments on lorries bound for the Gaza strip. These two examples are extreme, but they're examples that hopefully prompt us to try and understand the ideology that produced them rather than merely shake our heads. Nazis and Zionists aren't 'mindlessly' bloodthirsty, and most of them consider themselves civilised and morally sound. The Romans did too.

Perhaps knowing a little more about the ideology of the arena makes you more horrified that these children in Pompeii might have been watching real combats from the age of five. But when you think about it, children of all ages absorb or are explicitly taught some questionable stuff in every era, and that's how prejudice seeps into every new generation. Again, I'm not saying this is a good thing, but it's something that we need to delve deeper into in order to understand.

Perhaps, rather than clutching our pearls at the 'barbarity' of the past, we can use this to pause for a moment and consider what we're instilling into our own children in the 21st century, explicitly or otherwise. What messages are we giving them about our own concepts of gender roles? What are the virtues we urge them to foster? How are we answering the questions they are asking about life and death? What forms of entertainment do we deem appropriate? What levels of violence and dehumanisation do we deem socially acceptable? Who are we teaching our children to trust, whose authority to unquestionably accept? And this one is particularly relevant right now: whose deaths are we saying it is OK to witness or even cause?

wly discovered Pompeii graffiti reveals horrifying secret about brutal and bloody gladiator fights 2,000 years ago